Gentian

by Basil Rosa

It’s a day

when I believe everything important happens far, far away from where I stand. Two of my brothers, Mark and Steven, and I are shoveling our driveway yet again. We breathe, we work with such vigor. When I pause, I look up to the sky and see it washed metallic and bright and empty of clouds, and I think of it as the boldest, most memorable sky I’ve ever seen. I can also see and smell the ripples of heat radiating from the roof of our iced-up house with its eaves toothed with icicles, and I remember that Mother is in the kitchen baking two loaves of her date-nut bread—one for us boys and one to sell at an annual church fundraiser. Later in our socks and pajamas, we’ll sup greedily on canned tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwiches, and then we’ll each devour a wedge of cake covered in cream cheese. Father will come home after dark to find his driveway clear, and we’ll go to bed early to sleep in contentment and exhaustion.

It’s a night

when what returns before sleep is a memory of an Easter when it snowed a while and later, after our family meal in my brother Joe’s house in Sutton, sunshine came on, and the sky was that unique, cloudless presence again. But at that time in my life, it seemed chintzy somehow, not natural, and less than what I remembered it as. It drove me to realize there is no single moment when we happen.

I began

at age ten to run each morning, whipping through the woods on my way to school and imagining myself an Algonquin brave. The birds began to talk to me. I talked back, but I didn’t always listen. On rainy days after school, I lay on my stomach on the floor and read, until sleepy, from a new Highlights or a Boy’s Life each month, or dog and wilderness survival stories, or a Hardy Boys novel. On sunny days, having some marbles, an arrowhead, and a jackknife meant everything. Some of my marbles were as clear as that sky, and these I never traded but kept separately in a little tin that once held shoe polish.

I leaned

at age eleven into his long silences, buffed, waxed, and shining with admiration. Every fall I raked his lawn at least twice. He never paid me, nor did I expect it, but he’d give me a stamp now and then or wheat pennies, the rarer ones minted in San Francisco and Denver. We boys, my brothers and a bunch of kids in the neighborhood, would walk down the street with him and feel safe because he was so big and older, and we feared and idolized him. He did all the talking, mostly about PT boats and how fierce and honorable the Japanese fighters were in a place he called the Pacific Theatre and how they deserved our respect. How respect meant everything in this world.

Then one day

he just wasn’t around and my father had to explain that he’d left us for a better place and wouldn’t be coming back and that I should bring a plate of Mom’s home-baked cookies to his wife and just sit with her for a while. That plate was made of a glass that equaled the color and clarity of those skies I remembered.

I brought it to her, and we sat and ate cookies and drank hot chocolate and she washed the plate afterwards and I took it back to my mother. I didn’t tell anyone that I didn’t understand any of this. Nor did I know that such a color could have its own name.

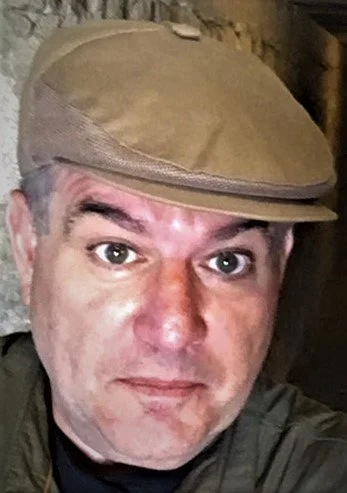

BIO: Basil Rosa writes from England. He also writes as John Michael Flynn, and his latest books are the short story collection, Vintage Vinyl Playlist, and the essay collection, How The Quiet Breathes. Find him at jmfbr1@blogspot.com, where he writes about other artists, authors and places he's been.