Scarecrow

by Robert L. Penick

The remote thunder of the approaching artillery grew more pronounced with each passing day. The air force was kaput, leaving the skies open to enemy bombers that thrummed overhead like heavy-laden bees. Most of the city looked deserted now. People cowered in cellars beneath bombed-out apartment blocks, emerging only to queue up in bread lines. Sometimes, this culminated in a rocket or shell from a railway gun, rending grandmothers and children into irregular meat. Wives and mothers remained hidden, for everyone knew what excesses capitulation would bring. For now, there were explosions and occasional bread, and a traitor hanging from a lamppost on every street. It was the first murmur of spring, and tiny green buds were appearing on the rare branch not culled for firewood.

This street, to the west of the river bisecting the city, was several kilometers away from any remaining military assets, so the main danger to this library was a mistaken artillery coordinate. Such things occasionally happened and geysers of dirt or cobblestone would throw themselves at heaven. Windows would crack, some panes would rattle in the wind, while others later fell out with no warning or reason, like suicides launching themselves from rooftops. Plaster had fallen from the ceiling, powdering the hardwood floors like sifted flour, and the chairs and tables harvested for fuel weeks ago. Yet, every book remained perfectly shelved, unblemished, and free of dust.

Scarecrow had been tending the premises since the librarians fled with the keys to the building and the large portrait of Our Leader that had hung ominously in the entrance hall. He didn’t miss Our Leader staring down at him, but—two weeks later—finally came to understand the theft of the painting: It’s much harder to execute those running away if they have both a plausible story and a huge likeness of the country’s savior on their backs. The keys were another story, however. The library held goods of great cultural value and even Scarecrow, a lowly janitor who could barely sign his own name, knew that. So he spent an entire day carrying stones, as large and heavy as children, into the cellar and up the stairs, creating an immense barricade that held the iron doors shut. When finished, he locked the cellar and slept for two days.

Goethe. The Sorrows of Young Werther. Scarecrow did not know it to be a classic of Western literature, but he knew his ABCs and, when he first discovered it on a table in a study lounge, started at the head of the first shelf and meticulously made the slow march down to the letter G. Then slowing further until Goethe, a row of gravestones running left to right. He scanned the titles before gently sliding the volume between Elective Affinities and The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily. There. It was home. He had never read a book. He couldn’t, but the order and dignity of the volumes surrounding him as he cleaned and tended the library filled him with reverence.

Food had become an abstract concept. There were times when the air was right—those moments he couldn’t imagine propellers flaying the sky on their way to the city—that he crept cautiously to nearby storefronts, ration card in hand. Queued up with 200 others, he would listen for death’s whistle like someone trying to recall a forgotten tune. Sometimes there was bread, sometimes a can of beets. Often, there was nothing, but the grandmothers and convalescents refused to believe this. If he obtained nourishment, he carried it under his fraying coat back to the library. Bread was eaten slowly over several days. Tins of food were squirreled away in the ductwork or behind massive encyclopedias. While the food stayed hidden, he made soup from wallpaper paste.

Where had everyone gone? The city was encircled, he had heard, ringed by troops even more vicious than his country’s own, who would torment the vanquished before dispatching them with a bullet or bayonet. This was the legend that hadn’t yet been realized locally, and it seemed to him this might not be true at all. But life was not so vital as the books, which—to him—were history and the future combined. He kept his vigil, made his rounds, and shifted whole sections away from where the roof let the rain in. No one visited, and no one tried to enter, since one can’t survive on books.

Scarecrow continued to waste away until his feet carried little weight at all. One afternoon in late April, he told his books, “My friends, I can do no more. You must continue on without me.” He made a nest behind the circulation desk, cradled an unopened tin can like a premature infant, and never moved again.

Soldiers found him on his back, eyes staring through the broken ceiling at blue sky, as white doves flitted, freely, from rafter to rafter.

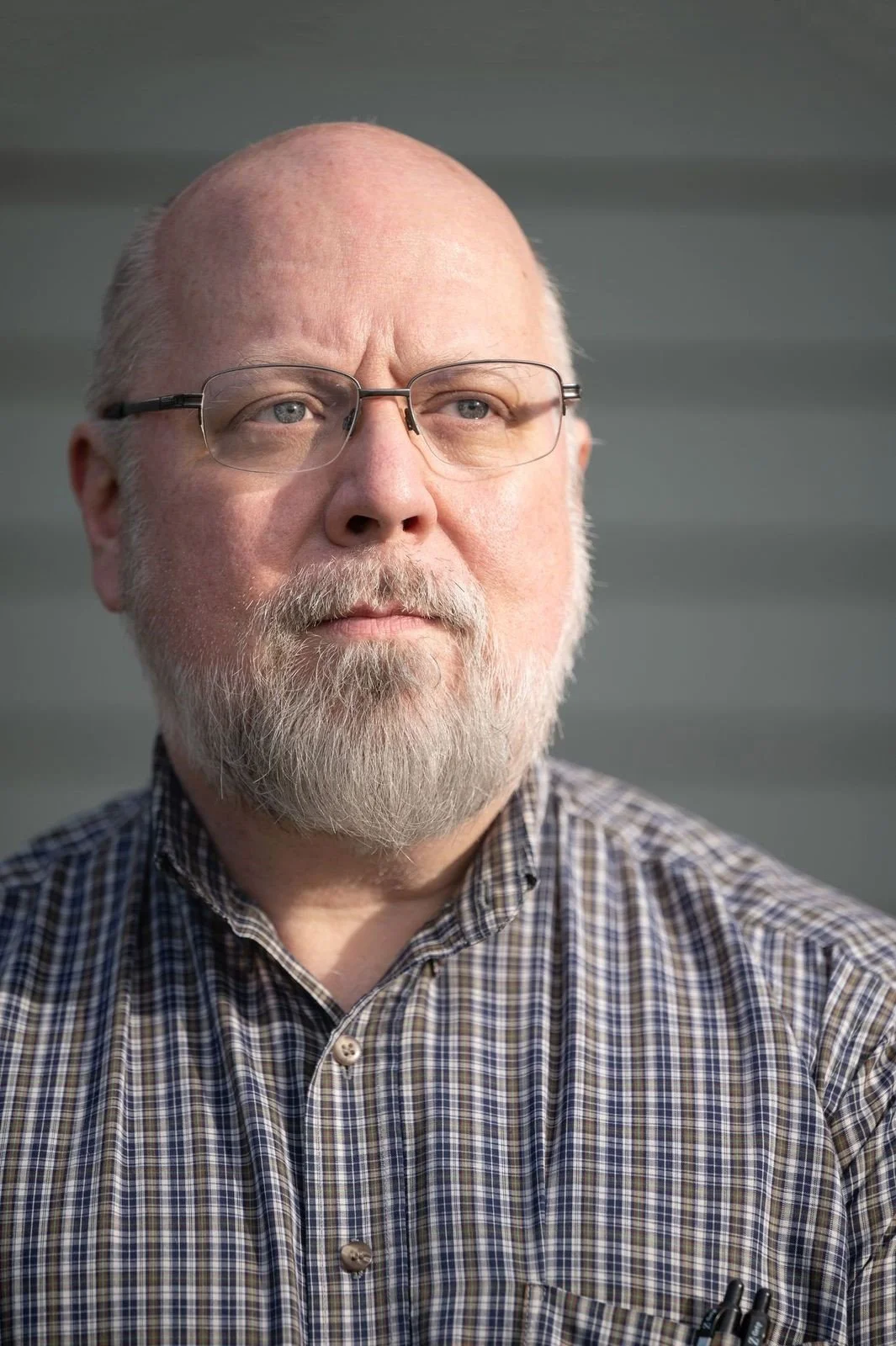

BIO: The poetry and prose of Robert L. Penick have appeared in well over 200 different literary journals, including The Hudson Review, North American Review, Plainsongs, and Oxford Magazine. The Art of Mercy: New and Selected Poems is now available from Hohm Press, and more of his work can be found at theartofmercy.net.